CHAPTER VII.

NORMAN'S TRIAL.

he destination of Norman and his companions was a small settlement at the lower end of Tyng Township called Goffe's Village, out of respect to one of its foremost inhabitants, John Goffe, afterward known as Colonel Goffe the Ranger.

This little hamlet stood at the mouth of a small stream known as Cohas Brook, which flowed into the Merrimack five miles below the Falls of Namaske.

Before reaching Goffe's Village, Norman and his companions passed a cross-road leading over the hill and toward the Scotch-Irish settlement on the east. About a mile up this road, at a point called "The Three Pines," or "Chestnut Corners," the shooting-match was expected to take place during the forenoon.

Tyng Township was settled during an interval of peace, there was no fort or garrison within its limits. Neither was there a public house of any kind, so Norman must be tried at the house of one of the most active inhabitants of the town, this having been arranged for by the Woodranger.

Somewhat to our hero's surprise, several persons were gathered about the house, as early as it was, and he knew by their looks and low-spoken speeches that they had been watching for his coming. In fact, though he did not know it, Gunwad had taken great pains to circulate the story of his arrest, and had boasted loudly that his trial would be worth attending. News of that kind travels fast, and, as short as the time had been, quite a crowd had collected, some coming several miles from the adjoining town, Londonderry, the former home of the Scotch-Irish now in Harrytown.

Among the others was a boy of fourteen, who attracted more than his share of attention. His name was Robert Rogers, and he was destined to be known within a few years, not only throughout New England but the entire country, as chief of that famous band of Indian fighters, " Rogers's Rangers." Already he was considered a crack shot with the rifle, and the fleetest runner in that vicinity. A strong bond of friendship bound him to the Woodranger, who had become his tutor in the secrets and hidden ways of woodcraft. No doubt he owed much of his future success to this early training. He was strongly and favourably impressed by the appearance of Norman, and he said aside to a companion:

"He's a likely youth ; and mind you, Mac, if they are overhard with him there's going to be trouble," an expression finding an echo in older hearts there, though the others were more cautious in their utterances.

"Hush, Robby!" admonished the boy's friend;

"say nothing rash. Captain Blanchard has the credit of being an extremely fair man, and, withal, one with a handy knack of getting out of a bad scrape easily. Here he comes, as prompt as usual."

Norman was being led into the house by Gunwad, who had now assumed charge of his prisoner. They were met at the door by a tall, rather austere appearing man, whom our hero knew by the little he had overheard was 'Squire Blanchard.

" You are promptly on hand, Goodman Gunwad," said the latter; "come right in this way," escorting the little party into the house, which was more commodious than most of the dwellings.

The deer reeve frowned at the salutation of Captain Blanchard, for it did not please him. Notwithstanding the simplicity of those times, a stronger class feeling existed than is known to-day. As a distinguishing term, the expression "Mister," which we apply without reserve or distinction, was given only to those who were looked upon as in the upper class, " Goodman" being used in its place when a person of supposed inferior position was addressed. The cause for Gunwad's vexation is apparent, as he aspired to rank higher than a " Goodman." But he thought it policy to conceal his chagrin, though no doubt it made him more irritable in the scenes which followed.

At the same time that the prisoner was led into the house by his captor, a small group of men, in the unmistakable dress of the Scotch-Irish, and headed by a tall, bony young man named John Hall, gathered about the door.

Woodranger nodded familiarly to these stern-looking men, but before entering the house he turned to speak to a medium-sized man, with the air of a woodsman and the breeding of a gentleman about him. He was none other than Captain Goffe, who, while he did not belong to the Tyng colony, was living in the midst of these men. It is safe to say that he was on friendly terms with every person present, or who might be there that day. The spectators, noticing this brief consultation between the forester and the soldier-scout, nodded their heads knowingly.

'Squire Blanchard then put an end to all conversation by saying:

" I understand this is your prisoner whom you charge with killing deer out of season, Goodman Gunwad ?"

" He is, cap'en."

" Are your witnesses all here ?"

"All I shall need, I reckon."

" Are your witnesses here, prisoner ? "

"I have none, sir."

" Then, unless objection is raised by the prisoner or the complainant, the case will be opened without further delay. I think there is a little matter several are anxious to attend to," alluding to the forthcoming shooting-match.

" Th' sooner th' better, cap'en," said Gunwad, showing by his appearance that he was well pleased. " I reckon it won't take long to salt his gravy."

" I understand you charge this young man, whose name I believe is McNiel — "

" A son, cap'en, of thet hated McNiel — "

" Silence, sir, while I am speaking ! " commanded "Squire Blanchard. " You charge this Norman McNiel with shooting deer out of season ? "

" I do, sir."

" You will take oath and then describe what reason you have for considering the prisoner guilty."

As soon as he had been properly sworn Gunwad went on to describe in his blunt, rough way how he had been attracted to Rock Rimmon by a gun-shot. Upon reaching the spot he had found a dead deer there, while the prisoner and his dog were the only living creatures that he saw in the vicinity. The youth's gun was empty, and he acknowledged his hound had started and followed the deer.

" I knowed the youngster o' a furriner," he concluded, " as the boy livin' with thet ol' refugee o' a MacDonald at the Falls, so I lost no time in clappin' my hands on him."

These allusions to Norman's father and grandfather it could be seen were given to antagonise, as much as possible, the Scotch-Irish spectators. But 'Squire Blanchard ended, or cut short, his speech by asking if he had witnesses to prove his statements.

" Woodranger here was with me, an' I reckon his word is erbout as good as enny the youngster can fetch erlong. Woodranger, step this way, an' tell th' 'squire whut ye know erbout this young poacher."

In answer to 'Squire Blanchard's request, but not to Gunwad's, the forester took the witness-stand, and, after being duly sworn, answered the questions asked him without hesitation or wavering.

" You were with Gunwad yesterday, Woodranger, when he met the prisoner at Rock Rimmon ? "

" I was, cap'en."

"And you saw the deer he had shot ?"

" I see the carcass o' a dead deer laying at the foot o' Rock Rimmon, cap'en."

" It was the deer the prisoner is supposed to have shot ? " asked 'Squire Blanchard, noticing the Wood-ranger's cautious way of replying.

" It was the only deer I see."

" You saw Gunwad take a bullet from its body ?"

" I did. I see, too, that the lead had not found a vital spot."

"Do you mean to say the deer was not killed by the shot ?"

"That's what I mean."

Gunwad was seen to scowl at this acknowledgment, while the spectators listened for the next question and reply in breathless eagerness.

" What was the cause of the creature's death, then ?"

" It was killed by its fall from Rock Rimmon. To be more correct, I should say its leap from the top of Rimmon, which you mus' know is a smart jump."

" But it was driven over the cliff by a hound at its heels ?"

" It could have gone round if it had wished. I 'low it was hard pressed, but it looked to me the critter took that way to get out o' a bad race."

A murmur of surprise ran around the crowded room, while Gunwad was heard to mutter an oath between his teeth.

" You say that for the benefit of the prisoner ?" demanded Blanchard, sharply.

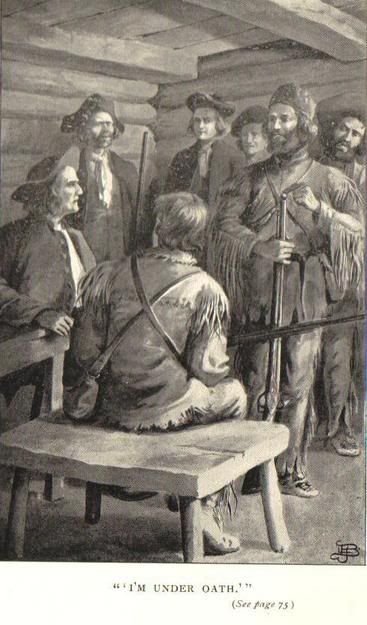

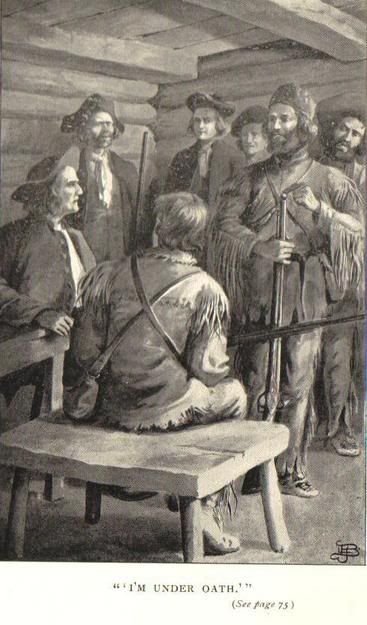

" I do not need to, cap'en. Besides, I'm under oath."

"Do you mean to say that a deer would jump off Rock Rimmon intent on its own destruction, Woodranger ? Now, as a man who lives in the forest, knows its most hidden secrets and worships its solitudes, answer me if you can."

Even Gunwad was silent now, and the knot of talkers outside the door, realising that the conversation between the justice and the witness had reached a point of more than ordinary interest, abruptly ended their discussion, to listen with the others.

" Cap'en Blanchard," said the Woodranger, in his simple, straightforward way, " I 'low I've spent a goodish portion o' my life in the woods, ranging 'em fur and wide it may be, sometime on the trail o' a red man, sometime stalking the deer, the bear, or the painter. Being a man not advarse to l'arning, though the little book wit I got inter my head onc't has slipped out, I have picked up some o' Natur's secrets. I can foller the Indian's trail where some might not read a sign. The trees tell me the way to go in the darkness o' night ; and the leaf forewarns me the weather for the morrer. If I do say it, and I think I may be pardoned for the boasting, few white men can show greater knack at trailing the Indian or stalking the four-footed critters o' the woods. My eye is trained to its mark, my hand to its work, and Ol' Danger here," tapping the barrel of his long rifle, " never has to bark the second time at the same critter. I hope you'll pardon me for saying all this, seeing no man has enny right to boast o' the knacks o' Natur'. If I have been a better scholard in her I school than in that o' man, it is because her teachings have been more to my heart. Her ways are ways of peace and read like an open book, but the ways o' man are ways o' consait and past finding out. Though I live by my rifle, I do not believe in wanton killing, and I never drew bead on critter with a malicious thought.

" But pardon me for so kivering the trail o' your question as not to find it. One is apt to study the manners o' 'em into whose company he is constantly thrown. So I have studied the ways o' the critters o' the woods very keerfully, to find 'em with many human traits. They have their joys and their sorrers, their loves and hates, their hopes and despairs, just like the human animal. In the wilds o' the North I once saw a sick buck walk deliberately up to the top o' a high bluff, and, after stopping a minute, while he seemed to be saying his prayers, jump to death on the rocks below. At another time, I sat and watched a leetle mole, old and sick, dig him a leetle hole in the earth, crawl in, and kiver himself over to die. I remember once I had a dog, and if I do say it, as knows best, he was the keenest hound on the scent and the truest fri'nd a man ever had. But at last his limbs come to be cramped with rheumatiz, his eyesight was no longer to be trusted, and his poor body wasted away for the food he had no appetite to eat. In his distress he lay down in my pathway, and asked me, in that language the more pathetic for lacking words, to put an end to his misery by a shot from my gun.

" I say, Cap'en Blanchard, I've witnessed sich as these, and, mind ye, while I do not pretend that deer leaped to its death o' its own free will on Rock Rimmon, in the light o' sich doings as I've known it might have done it rather than to find heels for the hound any longer."

Though the Woodranger had spoken at this great length, and in his roundabout manner, not a sound fell on the scene to break the clear flow of his voice. It was evident his wild, rude philosophy had taken effect in the rugged breasts of those hardy pioneers. Even 'Squire Blanchard paused for a considerable space before asking his next question.

" Granting all that, Woodranger, it has but slight bearing on the fact of the prisoner's guilt or innocence. I understand you to say it was his hound which had started the deer, and which was driving the creature that way — to its death, according to your own words."

" If I 'lowed as much as that, cap'en, I said more'n the truth will bear me out in. I will answer you by asking you a question."

" Go ahead in your way, Woodranger," consented the other. " I suppose I should accept from you what I would from no other person."

" Thank you, cap'en. This is the leetle p'int I've to unravel from my string o' knots: If a dog should come to your house and stop overnight, would that make him your dog for the rest o' his life ?"

"No."

"I figgered it that way. Wal, that deerhound, and he was a good one, come to this lad o' his own free will and stayed with him whether or no. Yesterday the critter took it into his head to start a deer from Cedar Swamp, and he did so without the knowledge o' the lad. The dog left, too, as soon as he see the mischief he'd done. Dogs may not understand man's laws, but they sometimes know when they have broke 'em."

" But there is no denying that the prisoner shot the animal ? " demanded 'Squire Blanchard, as if determined not to be beaten at every point.

" Not if that chunk o' lead will fit the bore o' his gun," holding out the bullet Gunwad had taken from the deer's body. "The lad has his gun with him, if I mistake not."

A ripple of excitement ran around the room at this speech, and Gunwad, as if fearing the trial was going contrary to his wishes, broke in with the exclamation, directed to no one in particular, but heard by all :

" This is er purty piece o' tomfoolery! "

Back to top

NORMAN'S TRIAL.

| T |

he destination of Norman and his companions was a small settlement at the lower end of Tyng Township called Goffe's Village, out of respect to one of its foremost inhabitants, John Goffe, afterward known as Colonel Goffe the Ranger.

This little hamlet stood at the mouth of a small stream known as Cohas Brook, which flowed into the Merrimack five miles below the Falls of Namaske.

Before reaching Goffe's Village, Norman and his companions passed a cross-road leading over the hill and toward the Scotch-Irish settlement on the east. About a mile up this road, at a point called "The Three Pines," or "Chestnut Corners," the shooting-match was expected to take place during the forenoon.

Tyng Township was settled during an interval of peace, there was no fort or garrison within its limits. Neither was there a public house of any kind, so Norman must be tried at the house of one of the most active inhabitants of the town, this having been arranged for by the Woodranger.

Somewhat to our hero's surprise, several persons were gathered about the house, as early as it was, and he knew by their looks and low-spoken speeches that they had been watching for his coming. In fact, though he did not know it, Gunwad had taken great pains to circulate the story of his arrest, and had boasted loudly that his trial would be worth attending. News of that kind travels fast, and, as short as the time had been, quite a crowd had collected, some coming several miles from the adjoining town, Londonderry, the former home of the Scotch-Irish now in Harrytown.

Among the others was a boy of fourteen, who attracted more than his share of attention. His name was Robert Rogers, and he was destined to be known within a few years, not only throughout New England but the entire country, as chief of that famous band of Indian fighters, " Rogers's Rangers." Already he was considered a crack shot with the rifle, and the fleetest runner in that vicinity. A strong bond of friendship bound him to the Woodranger, who had become his tutor in the secrets and hidden ways of woodcraft. No doubt he owed much of his future success to this early training. He was strongly and favourably impressed by the appearance of Norman, and he said aside to a companion:

"He's a likely youth ; and mind you, Mac, if they are overhard with him there's going to be trouble," an expression finding an echo in older hearts there, though the others were more cautious in their utterances.

"Hush, Robby!" admonished the boy's friend;

"say nothing rash. Captain Blanchard has the credit of being an extremely fair man, and, withal, one with a handy knack of getting out of a bad scrape easily. Here he comes, as prompt as usual."

Norman was being led into the house by Gunwad, who had now assumed charge of his prisoner. They were met at the door by a tall, rather austere appearing man, whom our hero knew by the little he had overheard was 'Squire Blanchard.

" You are promptly on hand, Goodman Gunwad," said the latter; "come right in this way," escorting the little party into the house, which was more commodious than most of the dwellings.

The deer reeve frowned at the salutation of Captain Blanchard, for it did not please him. Notwithstanding the simplicity of those times, a stronger class feeling existed than is known to-day. As a distinguishing term, the expression "Mister," which we apply without reserve or distinction, was given only to those who were looked upon as in the upper class, " Goodman" being used in its place when a person of supposed inferior position was addressed. The cause for Gunwad's vexation is apparent, as he aspired to rank higher than a " Goodman." But he thought it policy to conceal his chagrin, though no doubt it made him more irritable in the scenes which followed.

At the same time that the prisoner was led into the house by his captor, a small group of men, in the unmistakable dress of the Scotch-Irish, and headed by a tall, bony young man named John Hall, gathered about the door.

Woodranger nodded familiarly to these stern-looking men, but before entering the house he turned to speak to a medium-sized man, with the air of a woodsman and the breeding of a gentleman about him. He was none other than Captain Goffe, who, while he did not belong to the Tyng colony, was living in the midst of these men. It is safe to say that he was on friendly terms with every person present, or who might be there that day. The spectators, noticing this brief consultation between the forester and the soldier-scout, nodded their heads knowingly.

'Squire Blanchard then put an end to all conversation by saying:

" I understand this is your prisoner whom you charge with killing deer out of season, Goodman Gunwad ?"

" He is, cap'en."

" Are your witnesses all here ?"

"All I shall need, I reckon."

" Are your witnesses here, prisoner ? "

"I have none, sir."

" Then, unless objection is raised by the prisoner or the complainant, the case will be opened without further delay. I think there is a little matter several are anxious to attend to," alluding to the forthcoming shooting-match.

" Th' sooner th' better, cap'en," said Gunwad, showing by his appearance that he was well pleased. " I reckon it won't take long to salt his gravy."

" I understand you charge this young man, whose name I believe is McNiel — "

" A son, cap'en, of thet hated McNiel — "

" Silence, sir, while I am speaking ! " commanded "Squire Blanchard. " You charge this Norman McNiel with shooting deer out of season ? "

" I do, sir."

" You will take oath and then describe what reason you have for considering the prisoner guilty."

As soon as he had been properly sworn Gunwad went on to describe in his blunt, rough way how he had been attracted to Rock Rimmon by a gun-shot. Upon reaching the spot he had found a dead deer there, while the prisoner and his dog were the only living creatures that he saw in the vicinity. The youth's gun was empty, and he acknowledged his hound had started and followed the deer.

" I knowed the youngster o' a furriner," he concluded, " as the boy livin' with thet ol' refugee o' a MacDonald at the Falls, so I lost no time in clappin' my hands on him."

These allusions to Norman's father and grandfather it could be seen were given to antagonise, as much as possible, the Scotch-Irish spectators. But 'Squire Blanchard ended, or cut short, his speech by asking if he had witnesses to prove his statements.

" Woodranger here was with me, an' I reckon his word is erbout as good as enny the youngster can fetch erlong. Woodranger, step this way, an' tell th' 'squire whut ye know erbout this young poacher."

In answer to 'Squire Blanchard's request, but not to Gunwad's, the forester took the witness-stand, and, after being duly sworn, answered the questions asked him without hesitation or wavering.

" You were with Gunwad yesterday, Woodranger, when he met the prisoner at Rock Rimmon ? "

" I was, cap'en."

"And you saw the deer he had shot ?"

" I see the carcass o' a dead deer laying at the foot o' Rock Rimmon, cap'en."

" It was the deer the prisoner is supposed to have shot ? " asked 'Squire Blanchard, noticing the Wood-ranger's cautious way of replying.

" It was the only deer I see."

" You saw Gunwad take a bullet from its body ?"

" I did. I see, too, that the lead had not found a vital spot."

"Do you mean to say the deer was not killed by the shot ?"

"That's what I mean."

Gunwad was seen to scowl at this acknowledgment, while the spectators listened for the next question and reply in breathless eagerness.

" What was the cause of the creature's death, then ?"

" It was killed by its fall from Rock Rimmon. To be more correct, I should say its leap from the top of Rimmon, which you mus' know is a smart jump."

" But it was driven over the cliff by a hound at its heels ?"

" It could have gone round if it had wished. I 'low it was hard pressed, but it looked to me the critter took that way to get out o' a bad race."

A murmur of surprise ran around the crowded room, while Gunwad was heard to mutter an oath between his teeth.

" You say that for the benefit of the prisoner ?" demanded Blanchard, sharply.

" I do not need to, cap'en. Besides, I'm under oath."

"Do you mean to say that a deer would jump off Rock Rimmon intent on its own destruction, Woodranger ? Now, as a man who lives in the forest, knows its most hidden secrets and worships its solitudes, answer me if you can."

Even Gunwad was silent now, and the knot of talkers outside the door, realising that the conversation between the justice and the witness had reached a point of more than ordinary interest, abruptly ended their discussion, to listen with the others.

" Cap'en Blanchard," said the Woodranger, in his simple, straightforward way, " I 'low I've spent a goodish portion o' my life in the woods, ranging 'em fur and wide it may be, sometime on the trail o' a red man, sometime stalking the deer, the bear, or the painter. Being a man not advarse to l'arning, though the little book wit I got inter my head onc't has slipped out, I have picked up some o' Natur's secrets. I can foller the Indian's trail where some might not read a sign. The trees tell me the way to go in the darkness o' night ; and the leaf forewarns me the weather for the morrer. If I do say it, and I think I may be pardoned for the boasting, few white men can show greater knack at trailing the Indian or stalking the four-footed critters o' the woods. My eye is trained to its mark, my hand to its work, and Ol' Danger here," tapping the barrel of his long rifle, " never has to bark the second time at the same critter. I hope you'll pardon me for saying all this, seeing no man has enny right to boast o' the knacks o' Natur'. If I have been a better scholard in her I school than in that o' man, it is because her teachings have been more to my heart. Her ways are ways of peace and read like an open book, but the ways o' man are ways o' consait and past finding out. Though I live by my rifle, I do not believe in wanton killing, and I never drew bead on critter with a malicious thought.

" But pardon me for so kivering the trail o' your question as not to find it. One is apt to study the manners o' 'em into whose company he is constantly thrown. So I have studied the ways o' the critters o' the woods very keerfully, to find 'em with many human traits. They have their joys and their sorrers, their loves and hates, their hopes and despairs, just like the human animal. In the wilds o' the North I once saw a sick buck walk deliberately up to the top o' a high bluff, and, after stopping a minute, while he seemed to be saying his prayers, jump to death on the rocks below. At another time, I sat and watched a leetle mole, old and sick, dig him a leetle hole in the earth, crawl in, and kiver himself over to die. I remember once I had a dog, and if I do say it, as knows best, he was the keenest hound on the scent and the truest fri'nd a man ever had. But at last his limbs come to be cramped with rheumatiz, his eyesight was no longer to be trusted, and his poor body wasted away for the food he had no appetite to eat. In his distress he lay down in my pathway, and asked me, in that language the more pathetic for lacking words, to put an end to his misery by a shot from my gun.

" I say, Cap'en Blanchard, I've witnessed sich as these, and, mind ye, while I do not pretend that deer leaped to its death o' its own free will on Rock Rimmon, in the light o' sich doings as I've known it might have done it rather than to find heels for the hound any longer."

Though the Woodranger had spoken at this great length, and in his roundabout manner, not a sound fell on the scene to break the clear flow of his voice. It was evident his wild, rude philosophy had taken effect in the rugged breasts of those hardy pioneers. Even 'Squire Blanchard paused for a considerable space before asking his next question.

" Granting all that, Woodranger, it has but slight bearing on the fact of the prisoner's guilt or innocence. I understand you to say it was his hound which had started the deer, and which was driving the creature that way — to its death, according to your own words."

" If I 'lowed as much as that, cap'en, I said more'n the truth will bear me out in. I will answer you by asking you a question."

" Go ahead in your way, Woodranger," consented the other. " I suppose I should accept from you what I would from no other person."

" Thank you, cap'en. This is the leetle p'int I've to unravel from my string o' knots: If a dog should come to your house and stop overnight, would that make him your dog for the rest o' his life ?"

"No."

"I figgered it that way. Wal, that deerhound, and he was a good one, come to this lad o' his own free will and stayed with him whether or no. Yesterday the critter took it into his head to start a deer from Cedar Swamp, and he did so without the knowledge o' the lad. The dog left, too, as soon as he see the mischief he'd done. Dogs may not understand man's laws, but they sometimes know when they have broke 'em."

" But there is no denying that the prisoner shot the animal ? " demanded 'Squire Blanchard, as if determined not to be beaten at every point.

" Not if that chunk o' lead will fit the bore o' his gun," holding out the bullet Gunwad had taken from the deer's body. "The lad has his gun with him, if I mistake not."

A ripple of excitement ran around the room at this speech, and Gunwad, as if fearing the trial was going contrary to his wishes, broke in with the exclamation, directed to no one in particular, but heard by all :

" This is er purty piece o' tomfoolery! "

Back to top

<< Home