Thursday, March 13, 2008

Thursday, January 27, 2005

THE WOODRANGER

A STORY OF THE PIONEERS OF THE DEBATABLE GROUNDS

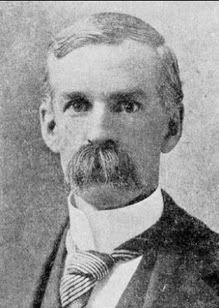

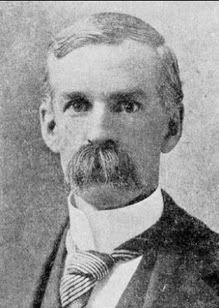

G. WALDO BROWNE

AUTHOR OF

"TWO AMERICAN BOYS IN HAWAII," ETC.

NEW YORK

A. WESSELS COMPANY

1907

Copyright, BY L. C. PAGE AND COMPANY

(Incorporated) All rights reserved

TO

Norman Stanley Browne

My merry little son hoping it will interest and instruct him this volume is most affectionately inscribed.

Edited by Nick Head Copyright 2005

CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTION ...... 7

I. THE DEER'S LEAP . . . . .11

II. THE WOODRANGER AND THE DEER REEVE.... 16

III. NORMAN MEETS HIS ENEMY ... 23

IV. A PERILOUS PREDICAMENT ... 30

V. JOHNNY STARK ...... 43

VI. THE MAN WHO KNEW IT ALL . . 53

VII. NORMAN'S TRIAL ..... 63

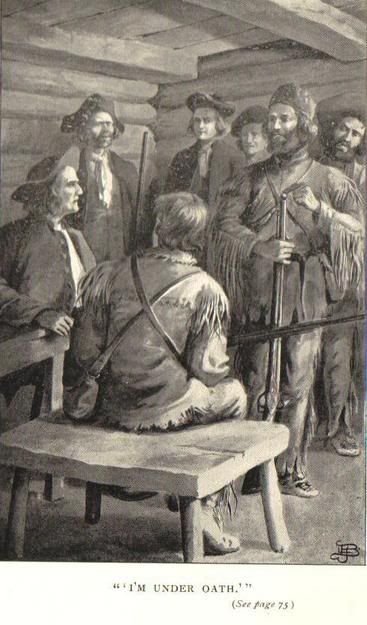

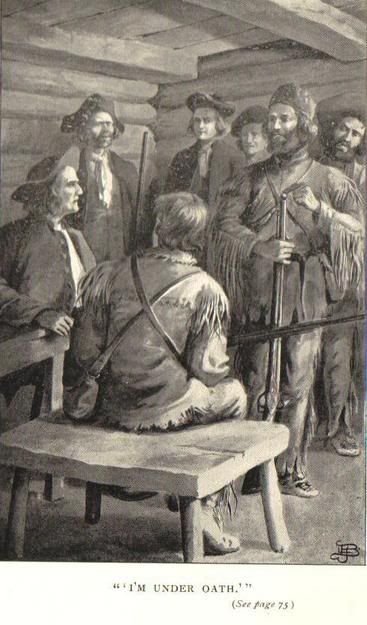

VIII. END OF THE TRIAL ..... 75

IX. THE SHOOTING-MATCH .... 84

X. AN ALARM ....... 97

XI. A FIERY GIRDLE ..... 103

XII. BAD NEWS AT HOME . . . .112

XIII. THE HONOUR OF THE McNIELS . .119

XIV. NORMAN WORKS IN A STUMP-FIELD . 126

XV. HANGING A BEAR ..... 139

XVI. GUNWAD TAKES DECISIVE ACTION . . 149

XVII. THE CANOE MATCH ..... 163

XVIII. THE FALL HUNT ..... 180

XIX. DEER NECK ...... 188

XX. THE CRY FOR HELP ..... 196

XXI. A PECULIAR PREDICAMENT 202

XXII. THE GUN-SHOT ...... 209

XXIII. THE FOREST TRAGEDY .... 215

XXIV. BEAR'S CLAWS — THE TURKEY TRAIN ...221

XXV. THE PLACE OF THE BIG BUCK... 229

XXVI. AROUND THE CAMP-FIRE .... 234

XXVII. "CREEPING" THE MOOSE . 242

XXVIII. THE BATTLE OF THE MONARCHS.... 250

XXIX. TEST SHOTS — THE SNOW-STORM... 255

XXX. THE BURNING OF CHRISTO'S WIGWAM.... 262

XXXI. THE WOODRANGER SURPRISES MR. MACDONALD ......270

XXXII. ZACK BITLOCK'S DEER . 278

XXXIII. RAISING THE MEETING-HOUSE . 286

XXXIV. THE FRESHET ...... 294

XXXV. THE WOODRANGER'S SECRET . 300

XXXVI. THE TURNING OF THE TIDE . 308

INTRODUCTION.

In order to understand the scenes about to be described, it is necessary to take a hasty glance at the general situation in 1740 of the colonists in the vicinity of the Merrimack River. It should be borne in mind that New England was only a narrow strip of country along the seacoast, and was divided into four provinces, — Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

Unfortunately for the welfare of the pioneers in the last-named province, the boundary line between New Hampshire and Massachusetts was a matter of dispute for nearly a hundred years. The difference had arisen from a misconception at the outset in regard to the source of the Merrimack River, which was believed by its early discoverers and explorers to rise in the

west and follow an easterly course to the ocean. Accordingly, the province of Massachusetts claimed not only all of the land to the southwest of the other province, but a strip three miles

wide along the east bank of the stream to its supposed source in the great lake (Winnepesaukee), including not only the debatable ground of Namaske, but a tract of country to its south and east,

called the " Chestnut Country," on account of the large number of those trees growing there.

In 1719 a part of this territory was settled by a party of colonists from the north of Ireland, known as Scotch-Irish, from their having previously emigrated to that country from Scotland.

These settlers, who called their new town first Nutfield and then Londonderry, in honour of the county from whence they had come, supposed that the deeds and grants which they had received from the province of New Hampshire would allow them to hold the debatable ground. They were upright, courageous men and women, but were rigid Presbyterians, and for this reason met with little favour from their equally austere Puritan neighbours from Massachusetts.

In order to colonise the disputed territory, Massachusetts at about this time began a system of granting lands as a reward for meritorious service in fighting the Indians, and among others

was a grant to the survivors of the famous " Snow Shoe Expedition " of the tract of land below Namaske Falls, which had gained the disreputable name of Old Harrytown. The leader of the

expedition, Captain Tyng, was dead, but in honour of him the new town was named Tyng Township.

In one respect the settlers of Tyng Township were fortunate. They arrived during one of those transitory intervals of comparative peace, which came and went during the long and sanguinary struggle with the Indians like flashes of sunlight on a stormy clay. In 1725, following several victories of the whites over their savage enemies, foremost of which was Lovewell's fight, the chief of the Abnaki Indians, then the leading tribe in New England, signed a treaty of peace at

Boston. This treaty was not broken until 1744, and the whole history of Tyng Township is included within these two dates.

As stated above, some of the Scotch-Irish, under grants from New Hampshire, had already settled in the territory granted by Massachusetts to Tyng's men, and an intense rivalry at once

sprang up between the settlements. The English were determined and aggressive, the Scotch stubborn and ready to fight to the bitter end for what they considered their rights, and before

long both sides were ready to resort to arms the moment an overt act of their rivals should seem to call for such measures.

G. WALDO BROWNE.

Back to top

A STORY OF THE PIONEERS OF THE DEBATABLE GROUNDS

G. WALDO BROWNE

AUTHOR OF

"TWO AMERICAN BOYS IN HAWAII," ETC.

NEW YORK

A. WESSELS COMPANY

1907

Copyright, BY L. C. PAGE AND COMPANY

(Incorporated) All rights reserved

TO

Norman Stanley Browne

My merry little son hoping it will interest and instruct him this volume is most affectionately inscribed.

Edited by Nick Head Copyright 2005

CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTION ...... 7

I. THE DEER'S LEAP . . . . .11

II. THE WOODRANGER AND THE DEER REEVE.... 16

III. NORMAN MEETS HIS ENEMY ... 23

IV. A PERILOUS PREDICAMENT ... 30

V. JOHNNY STARK ...... 43

VI. THE MAN WHO KNEW IT ALL . . 53

VII. NORMAN'S TRIAL ..... 63

VIII. END OF THE TRIAL ..... 75

IX. THE SHOOTING-MATCH .... 84

X. AN ALARM ....... 97

XI. A FIERY GIRDLE ..... 103

XII. BAD NEWS AT HOME . . . .112

XIII. THE HONOUR OF THE McNIELS . .119

XIV. NORMAN WORKS IN A STUMP-FIELD . 126

XV. HANGING A BEAR ..... 139

XVI. GUNWAD TAKES DECISIVE ACTION . . 149

XVII. THE CANOE MATCH ..... 163

XVIII. THE FALL HUNT ..... 180

XIX. DEER NECK ...... 188

XX. THE CRY FOR HELP ..... 196

XXI. A PECULIAR PREDICAMENT 202

XXII. THE GUN-SHOT ...... 209

XXIII. THE FOREST TRAGEDY .... 215

XXIV. BEAR'S CLAWS — THE TURKEY TRAIN ...221

XXV. THE PLACE OF THE BIG BUCK... 229

XXVI. AROUND THE CAMP-FIRE .... 234

XXVII. "CREEPING" THE MOOSE . 242

XXVIII. THE BATTLE OF THE MONARCHS.... 250

XXIX. TEST SHOTS — THE SNOW-STORM... 255

XXX. THE BURNING OF CHRISTO'S WIGWAM.... 262

XXXI. THE WOODRANGER SURPRISES MR. MACDONALD ......270

XXXII. ZACK BITLOCK'S DEER . 278

XXXIII. RAISING THE MEETING-HOUSE . 286

XXXIV. THE FRESHET ...... 294

XXXV. THE WOODRANGER'S SECRET . 300

XXXVI. THE TURNING OF THE TIDE . 308

INTRODUCTION.

In order to understand the scenes about to be described, it is necessary to take a hasty glance at the general situation in 1740 of the colonists in the vicinity of the Merrimack River. It should be borne in mind that New England was only a narrow strip of country along the seacoast, and was divided into four provinces, — Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire.

Unfortunately for the welfare of the pioneers in the last-named province, the boundary line between New Hampshire and Massachusetts was a matter of dispute for nearly a hundred years. The difference had arisen from a misconception at the outset in regard to the source of the Merrimack River, which was believed by its early discoverers and explorers to rise in the

west and follow an easterly course to the ocean. Accordingly, the province of Massachusetts claimed not only all of the land to the southwest of the other province, but a strip three miles

wide along the east bank of the stream to its supposed source in the great lake (Winnepesaukee), including not only the debatable ground of Namaske, but a tract of country to its south and east,

called the " Chestnut Country," on account of the large number of those trees growing there.

In 1719 a part of this territory was settled by a party of colonists from the north of Ireland, known as Scotch-Irish, from their having previously emigrated to that country from Scotland.

These settlers, who called their new town first Nutfield and then Londonderry, in honour of the county from whence they had come, supposed that the deeds and grants which they had received from the province of New Hampshire would allow them to hold the debatable ground. They were upright, courageous men and women, but were rigid Presbyterians, and for this reason met with little favour from their equally austere Puritan neighbours from Massachusetts.

In order to colonise the disputed territory, Massachusetts at about this time began a system of granting lands as a reward for meritorious service in fighting the Indians, and among others

was a grant to the survivors of the famous " Snow Shoe Expedition " of the tract of land below Namaske Falls, which had gained the disreputable name of Old Harrytown. The leader of the

expedition, Captain Tyng, was dead, but in honour of him the new town was named Tyng Township.

In one respect the settlers of Tyng Township were fortunate. They arrived during one of those transitory intervals of comparative peace, which came and went during the long and sanguinary struggle with the Indians like flashes of sunlight on a stormy clay. In 1725, following several victories of the whites over their savage enemies, foremost of which was Lovewell's fight, the chief of the Abnaki Indians, then the leading tribe in New England, signed a treaty of peace at

Boston. This treaty was not broken until 1744, and the whole history of Tyng Township is included within these two dates.

As stated above, some of the Scotch-Irish, under grants from New Hampshire, had already settled in the territory granted by Massachusetts to Tyng's men, and an intense rivalry at once

sprang up between the settlements. The English were determined and aggressive, the Scotch stubborn and ready to fight to the bitter end for what they considered their rights, and before

long both sides were ready to resort to arms the moment an overt act of their rivals should seem to call for such measures.

G. WALDO BROWNE.

Back to top

CHAPTER I.

THE DEER'S LEAP

s the distant baying of a hound broke like a discordant note upon the quiet of the summer afternoon, a youth sprang upright on the pinnacle of a cliff which reared its bald head above the surrounding forest, and listened for a repetition of the unexpected alarm.

The young listener presented a striking figure, the strong physique of limb and body brought into bold relief against the sky, and each feature clearly outlined, as he gazed into space. He was in his nineteenth year, above the medium height, but so symmetrical in form that he did not look out of proportion. His high cheek-bones, clear blue eyes, straight nose, well-curved chin, and firm-set mouth showed the characteristics of the Lowland sons of old Scotland. His name was Norman McNiel.

For nearly an hour he had lain there on the summit of Rock Rimmon, gazing in a dreamy way over the broad panorama of wilderness, while his mind carried him back across the stormy sea to his early home in Northern Ireland, which he had left a year before to come to this country with his young foster-sister Rilma and their aged grandfather, Robert MacDonald, last of the noted MacDonalds of Glencoe.

" It was Archer's bark ! " he exclaimed. " He must have followed me, and now has started a deer from its favourite haunt in Cedar Swamp. Hark! there he sounds his warning again, and never bugle of bold clansman rang clearer over the braes o' bonny Scotland. He is coming this way! Forsooth! A bonny hunter am I with not a grain of powder in my horn, and the last bullet sent on a fruitless errand after a wild bird. A pretty kettle of fish is this for a McNiel! "

Another cry from the hound at that moment, clearer, louder, nearer, held his entire attention, and sent the warm blood tingling through his veins. Far and wide over the valley rang the deep bass baying of the hound, the wooded hills on either side catching up the wild sound, and flinging it back and forth,until it seemed as if a dozen dogs were on the heels of some poor hunted victim.

The chase continued to draw swiftly nearer and nearer,' As if the race had become too earnest for it to keep up its running outcries, only an occasional short, sharp cry came from the hound. Soon this too ceased, and Norman was beginning to fear the chase was taking another course, when the sharp report of a firearm awoke the silence.

A howl from the hound quickly followed, while this was succeeded by a more pitiful cry, and the furious crashing of bodies plunging headlong through the thick undergrowth.

Immediately succeeding the renewed baying of the hound, Norman became aware of the sound of some one pushing his way rapidly through the growth off to his right, and at an acute angle to the course being taken by the deer. The next moment he was surprised to see a human figure burst into the opening at the lower end of the cliff, apparently making for the summit of Rock Rimmon. His surprise was heightened by a second discovery swiftly following the first. The newcomer was an Indian, carrying In his hand the gun with which he had shot at the deer.

Seeing Norman, instead of approaching any nearer the cliff, the red man abruptly changed his course, disappearing the next moment in the forest with the Indian's peculiar loping gait.

" Christo, the last of the Pennacooks ! " exclaimed Norman. " It was he who fired the shot. I — "

He was cut short in the midst of his speculation by the sudden appearance of the hunted deer on the opposite side of the clearing.

Though Rock Rimmon has a sheer descent of nearly a hundred feet on the south, its ascent is so gradual on the north as to make it an easy feat to reach its top. A growth of stunted pitch-pines grew to within fifty yards of Norman's standing place. The ledge was covered with moss in spots, while here and there a scrubby oak found a precarious living.

Although expecting to get a sight of the deer, as he imagined the fugitive to be, Norman was still considerably surprised to see the hunted creature bound out from the matted pines, and leap straight up the rocky pathway! Close upon its heels followed the hound, no longer keeping up its resonant baying.

The fugitive deer seemed to have a purpose in pursuing this narrow course, as it might have turned slightly to the right or left, and escaped its inevitable fate on the cliff. The large, lustrous eyes, glancing wildly around, saw nothing clearly. The blood was flowing freely from its panting sides, and it was evident its strength was nearly spent. To Norman, who had seen but a few of its kind, there was a human expression in the soft light of its great, mournful eye, and intuitively he shrank back, as he saw the doomed creature approaching.

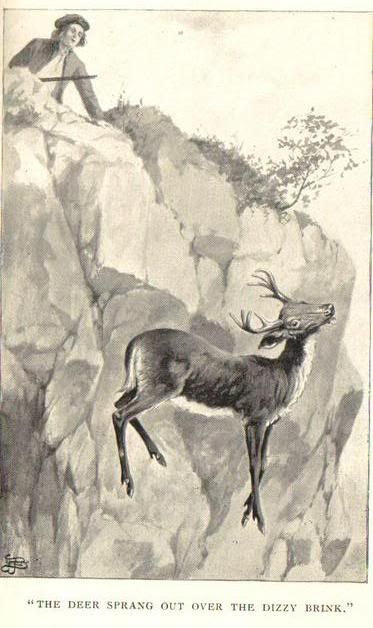

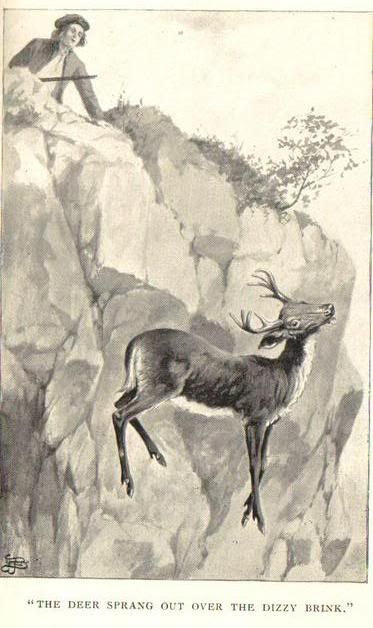

In its fatal alarm the terrified animal had not seen him. In fact it seemed to see nothing in its pathway, — not even the precipice cutting off further retreat. As if preferring death by a mad leap over the chasm, it sped to the very brink without checking the speed of its flying feet ! Norman held his breath with a feeling of horror at the inevitable fate of the poor creature. The hound, as if realising the desperate strait to which it had driven its prey, stopped. Then, with a last mournful glance backward, and a sharp cry of pain and despair, the deer sprang out over the dizzy brink, its beautiful form sinking swiftly upon the stony earth at the foot of Rock Rimmon!

Back to top

THE DEER'S LEAP

| A |

s the distant baying of a hound broke like a discordant note upon the quiet of the summer afternoon, a youth sprang upright on the pinnacle of a cliff which reared its bald head above the surrounding forest, and listened for a repetition of the unexpected alarm.

The young listener presented a striking figure, the strong physique of limb and body brought into bold relief against the sky, and each feature clearly outlined, as he gazed into space. He was in his nineteenth year, above the medium height, but so symmetrical in form that he did not look out of proportion. His high cheek-bones, clear blue eyes, straight nose, well-curved chin, and firm-set mouth showed the characteristics of the Lowland sons of old Scotland. His name was Norman McNiel.

For nearly an hour he had lain there on the summit of Rock Rimmon, gazing in a dreamy way over the broad panorama of wilderness, while his mind carried him back across the stormy sea to his early home in Northern Ireland, which he had left a year before to come to this country with his young foster-sister Rilma and their aged grandfather, Robert MacDonald, last of the noted MacDonalds of Glencoe.

" It was Archer's bark ! " he exclaimed. " He must have followed me, and now has started a deer from its favourite haunt in Cedar Swamp. Hark! there he sounds his warning again, and never bugle of bold clansman rang clearer over the braes o' bonny Scotland. He is coming this way! Forsooth! A bonny hunter am I with not a grain of powder in my horn, and the last bullet sent on a fruitless errand after a wild bird. A pretty kettle of fish is this for a McNiel! "

Another cry from the hound at that moment, clearer, louder, nearer, held his entire attention, and sent the warm blood tingling through his veins. Far and wide over the valley rang the deep bass baying of the hound, the wooded hills on either side catching up the wild sound, and flinging it back and forth,until it seemed as if a dozen dogs were on the heels of some poor hunted victim.

The chase continued to draw swiftly nearer and nearer,' As if the race had become too earnest for it to keep up its running outcries, only an occasional short, sharp cry came from the hound. Soon this too ceased, and Norman was beginning to fear the chase was taking another course, when the sharp report of a firearm awoke the silence.

A howl from the hound quickly followed, while this was succeeded by a more pitiful cry, and the furious crashing of bodies plunging headlong through the thick undergrowth.

Immediately succeeding the renewed baying of the hound, Norman became aware of the sound of some one pushing his way rapidly through the growth off to his right, and at an acute angle to the course being taken by the deer. The next moment he was surprised to see a human figure burst into the opening at the lower end of the cliff, apparently making for the summit of Rock Rimmon. His surprise was heightened by a second discovery swiftly following the first. The newcomer was an Indian, carrying In his hand the gun with which he had shot at the deer.

Seeing Norman, instead of approaching any nearer the cliff, the red man abruptly changed his course, disappearing the next moment in the forest with the Indian's peculiar loping gait.

" Christo, the last of the Pennacooks ! " exclaimed Norman. " It was he who fired the shot. I — "

He was cut short in the midst of his speculation by the sudden appearance of the hunted deer on the opposite side of the clearing.

Though Rock Rimmon has a sheer descent of nearly a hundred feet on the south, its ascent is so gradual on the north as to make it an easy feat to reach its top. A growth of stunted pitch-pines grew to within fifty yards of Norman's standing place. The ledge was covered with moss in spots, while here and there a scrubby oak found a precarious living.

Although expecting to get a sight of the deer, as he imagined the fugitive to be, Norman was still considerably surprised to see the hunted creature bound out from the matted pines, and leap straight up the rocky pathway! Close upon its heels followed the hound, no longer keeping up its resonant baying.

The fugitive deer seemed to have a purpose in pursuing this narrow course, as it might have turned slightly to the right or left, and escaped its inevitable fate on the cliff. The large, lustrous eyes, glancing wildly around, saw nothing clearly. The blood was flowing freely from its panting sides, and it was evident its strength was nearly spent. To Norman, who had seen but a few of its kind, there was a human expression in the soft light of its great, mournful eye, and intuitively he shrank back, as he saw the doomed creature approaching.

In its fatal alarm the terrified animal had not seen him. In fact it seemed to see nothing in its pathway, — not even the precipice cutting off further retreat. As if preferring death by a mad leap over the chasm, it sped to the very brink without checking the speed of its flying feet ! Norman held his breath with a feeling of horror at the inevitable fate of the poor creature. The hound, as if realising the desperate strait to which it had driven its prey, stopped. Then, with a last mournful glance backward, and a sharp cry of pain and despair, the deer sprang out over the dizzy brink, its beautiful form sinking swiftly upon the stony earth at the foot of Rock Rimmon!

Back to top

CHAPTER II.

THE WOODRANGER AND THE DEER REEVE.

o sudden and strange was the leap to death of the hunted deer, that Norman McNiel stood for a moment stupefied by a sense of horror at the strange sight. The hound, a magnificent animal, as if sharing its master's feeling with an added shame for the part it had taken in the matter, crept to his side, and sank silently upon the rock at his feet.

" He escaped you, Archer," said the young master, patting the dog on its head, "and me, too, for that matter. But I cannot see that either was to blame. The poor creature met his fate bravely."

Then, to satisfy himself that the deer was really killed, he approached to the extremity of the cliff, and peered into the depths below. He discovered, at his first glance, the mutilated form of the creature. There could be no doubt of its death. The sound of footsteps at that instant arrested his attention. Looking from the shapeless body of the deer, he saw two men pushing their way through the dense growth skiting the bit of clearing at the foot of the ledge.

The foremost of the newcomers was an entire stranger to him, though he guessed that he belonged Tyng colonists, who had settled below the falls. He wore a suit of clothes made from the homespun cloth so common among the Massachusetts men, and his firearm was of the English pattern usually carried by them. He was not much, if any, over thirty years of age, with a countenance of its slight share of good looks by a stubble of reddish beard.

His companion, whom Norman remembered as having seen once or twice the previous season, was several years the senior of the other, and of altogether different appearance. He was clad in a wellworn suit of buckskin, the frills on the leggins badly frayed from long contact with the briars and brushwood of the forest. His feet were encased in a pair Indian moccasins, while he wore on his head a cap of fox skin, with the tail of the animal hanging down to the back of his neck. Though bronzed by long exposure to the summer sun and winter wind, scarred by wounds, and rendered shaggy by its untrimmed beard, his face bore that stamp of frank,honest simplicity which was sure to win for the the respect and confidence of those he met.

The silver streaks in the hair falling in profusion about his neck told that he was passing the prime of life. Still there was great strength in the long, muscular limbs, and, while he moved generally with a slow, shuffling gait, he was capable of astonishing swiftness of movement whenever it was called for.

He showed his natural instinct as a woodsman by the noiseless way in which he emerged from the forest, in marked contrast to the slouching steps of his companion. Stuck in his belt could be seen the handle of a serviceable knife, while he carried a heavy, long-barrelled rifle of a pattern unknown in this vicinity at that time. The weapon showed that it had seen long and hard service.

Norman was about to speak to him, when the other exclaimed, in the tone of one announcing an important discovery :

" Look there, Woodranger ! if you want to believe me. It's the critter that got the shot we heerd, and it's a deer as I told ye. A shot out o' season, too, mind ye, Woodranger. If I could clap my eyes on the fool he'd walk to Chelmsford with me

to-morrer, or I ain't deer reeve o' this grant o' Tyng Township, honourably and discreetly 'p'inted by the Gineral Court o' the Province o' Massachusetts."

"It seems to me, Gunwad," said his companion, speaking in a more deliberate tone, as he advanced to the deer's mutilated form, " that the creetur must have taken a powerful tumble over the rock hyur. I reckon a jump off'n Rock Rimmon would be nigh bout enough to stop the breath o' most any deer."

" What made the deer jump off'n the rock, Woodranger ? It was thet air dog at its heels! And ef there ain't a hunk o' lead in the critter big ernough to send the man thet fired it to Chelmsford I'll eat the carcass, hoofs, horns, and, hide."

With these words he bent over the still warm body of the deer, and began a diligent search for some sign of the wound supposed to have been made by the shot.

Woodranger dropped the butt of his rifle upon the ground, and stood leaning on its muzzle, while he Watched with curious interest the proceeding of his Companion.

Gunwad's search was not made in vain, for a minute later he held up between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand, which was reeking with blood from its contact with the dead deer, the bullet he had hoped to find.

" What do you think of it now ?" he demanded, showing by his tone and manner that he was highly pleased with his discovery. " What do ye call thet ?"

" I suppose it would require no great knowledge o' warfare to pronounce it a bullet, — leastways a pellet o' lead fit for the weepon o' a red. It was never the bullet o' a white man's gun. But that does not enter into the question. That bullet was not the death o' this deer."

" You're talking at random now. Mebbe it didn't kill the deer, but ef the dog hadn't driven the critter over the rock, thet lead would hev fixed it for salting."

"I'm not so sure o' that, friend Gunwad. If you'll look a leetle cluser you'll see that the bullet didn't touch any vital. It sort o' slewed up'ards and side— "

"Much has thet got to do erbout it!" broke in Gunwad, beginning to show anger. " I shall begin to think ye air consarned in the matter. Fust ye say it wasn't the bullit o' a white man, and I should like to know what cause ye hev for saying thet."

"It was never run by any mould," replied Wood-ranger, calmly, as he took the bullet in his hand; " it was hammered out."

"Say!" exclaimed Gunwad, suddenly changing the drift of the conversation, "Ye're a sharp one, Woodranger. They say ye're the best guide and Injun trailer in the two provinces. Help me fasten this bizness on that Injun at the Falls, and I'll gin ye the best pair o' beaver skins ye ever sot eyes on for years."

" You mean Christo," said the other.

"I reckon he's the only red left in these parts, and 'arly riddance to him ! Jess show thet is an Injun bullit, and I've settled his 'count, sure's one and one make two."

" That savours too much o' wanton killing, Gunwad. I ain't no special grudge ag'in this Christo, though it may be I have leetle fellowship for the face. There be honest men, for all I can say, among the dusky-skins, and Christo may be one o' 'em. At any rate till I ketch him in red devilryment I'm not going to condemn him. Ah, Gunwad, I 'low I live by the chase, and if I do say it, who has no designment to boast o' the simple knack o' drawing bead on wildcat or painter, bear or stag, Old Danger never barks at the same creetur but once; but he never spits fire in the face o' any creetur that can't do more good by dying than living."

"Look here, Woodranger!" exclaimed Gunwad, impatiently, "I can see through yer logic. Ye air ag'in this law o' protecting deer."

" I'm ag'in the law that's ag'in man. 'Tain't natur to fill the woods with game, and then blaze the trees with notices not to tech a creetur. Mind you, I'm ag'in wanton killing, and him don't live as can say I ever drew bead on a deer out o' pure malice. I have noticed that it's the same chaps as makes these laws as are the ones to resort to wanton destruction. To kill jess for the fun o' killing is wanton. It is the great law o' natur for one kind to war on another, the strong on the weak, from the biggest brute to the smallest worm, and man wars on 'em all. If he must do so, let there be as much fairness as is consistent with human natur. No, I'm not a liker o' the law that professes to defend the helpless, but does it so the wanton slayer can get his glut o' slaughter in a fall's hunt. I — "

The Woodranger might have continued his rude philosophy much longer had not a movement of the hound on the cliff attracted their attention, and both men glanced upward to see, with surprise, Norman McNiel looking quietly down upon them.

" Hilloa! " exclaimed Gunwad, divining the situation at once, "here is the deer slayer, or I'm a fool. Stand where ye air, youngster! " raising his gun to his shoulder, as he spoke.

Back to top

THE WOODRANGER AND THE DEER REEVE.

| S |

o sudden and strange was the leap to death of the hunted deer, that Norman McNiel stood for a moment stupefied by a sense of horror at the strange sight. The hound, a magnificent animal, as if sharing its master's feeling with an added shame for the part it had taken in the matter, crept to his side, and sank silently upon the rock at his feet.

" He escaped you, Archer," said the young master, patting the dog on its head, "and me, too, for that matter. But I cannot see that either was to blame. The poor creature met his fate bravely."

Then, to satisfy himself that the deer was really killed, he approached to the extremity of the cliff, and peered into the depths below. He discovered, at his first glance, the mutilated form of the creature. There could be no doubt of its death. The sound of footsteps at that instant arrested his attention. Looking from the shapeless body of the deer, he saw two men pushing their way through the dense growth skiting the bit of clearing at the foot of the ledge.

The foremost of the newcomers was an entire stranger to him, though he guessed that he belonged Tyng colonists, who had settled below the falls. He wore a suit of clothes made from the homespun cloth so common among the Massachusetts men, and his firearm was of the English pattern usually carried by them. He was not much, if any, over thirty years of age, with a countenance of its slight share of good looks by a stubble of reddish beard.

His companion, whom Norman remembered as having seen once or twice the previous season, was several years the senior of the other, and of altogether different appearance. He was clad in a wellworn suit of buckskin, the frills on the leggins badly frayed from long contact with the briars and brushwood of the forest. His feet were encased in a pair Indian moccasins, while he wore on his head a cap of fox skin, with the tail of the animal hanging down to the back of his neck. Though bronzed by long exposure to the summer sun and winter wind, scarred by wounds, and rendered shaggy by its untrimmed beard, his face bore that stamp of frank,honest simplicity which was sure to win for the the respect and confidence of those he met.

The silver streaks in the hair falling in profusion about his neck told that he was passing the prime of life. Still there was great strength in the long, muscular limbs, and, while he moved generally with a slow, shuffling gait, he was capable of astonishing swiftness of movement whenever it was called for.

He showed his natural instinct as a woodsman by the noiseless way in which he emerged from the forest, in marked contrast to the slouching steps of his companion. Stuck in his belt could be seen the handle of a serviceable knife, while he carried a heavy, long-barrelled rifle of a pattern unknown in this vicinity at that time. The weapon showed that it had seen long and hard service.

Norman was about to speak to him, when the other exclaimed, in the tone of one announcing an important discovery :

" Look there, Woodranger ! if you want to believe me. It's the critter that got the shot we heerd, and it's a deer as I told ye. A shot out o' season, too, mind ye, Woodranger. If I could clap my eyes on the fool he'd walk to Chelmsford with me

to-morrer, or I ain't deer reeve o' this grant o' Tyng Township, honourably and discreetly 'p'inted by the Gineral Court o' the Province o' Massachusetts."

"It seems to me, Gunwad," said his companion, speaking in a more deliberate tone, as he advanced to the deer's mutilated form, " that the creetur must have taken a powerful tumble over the rock hyur. I reckon a jump off'n Rock Rimmon would be nigh bout enough to stop the breath o' most any deer."

" What made the deer jump off'n the rock, Woodranger ? It was thet air dog at its heels! And ef there ain't a hunk o' lead in the critter big ernough to send the man thet fired it to Chelmsford I'll eat the carcass, hoofs, horns, and, hide."

With these words he bent over the still warm body of the deer, and began a diligent search for some sign of the wound supposed to have been made by the shot.

Woodranger dropped the butt of his rifle upon the ground, and stood leaning on its muzzle, while he Watched with curious interest the proceeding of his Companion.

Gunwad's search was not made in vain, for a minute later he held up between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand, which was reeking with blood from its contact with the dead deer, the bullet he had hoped to find.

" What do you think of it now ?" he demanded, showing by his tone and manner that he was highly pleased with his discovery. " What do ye call thet ?"

" I suppose it would require no great knowledge o' warfare to pronounce it a bullet, — leastways a pellet o' lead fit for the weepon o' a red. It was never the bullet o' a white man's gun. But that does not enter into the question. That bullet was not the death o' this deer."

" You're talking at random now. Mebbe it didn't kill the deer, but ef the dog hadn't driven the critter over the rock, thet lead would hev fixed it for salting."

"I'm not so sure o' that, friend Gunwad. If you'll look a leetle cluser you'll see that the bullet didn't touch any vital. It sort o' slewed up'ards and side— "

"Much has thet got to do erbout it!" broke in Gunwad, beginning to show anger. " I shall begin to think ye air consarned in the matter. Fust ye say it wasn't the bullit o' a white man, and I should like to know what cause ye hev for saying thet."

"It was never run by any mould," replied Wood-ranger, calmly, as he took the bullet in his hand; " it was hammered out."

"Say!" exclaimed Gunwad, suddenly changing the drift of the conversation, "Ye're a sharp one, Woodranger. They say ye're the best guide and Injun trailer in the two provinces. Help me fasten this bizness on that Injun at the Falls, and I'll gin ye the best pair o' beaver skins ye ever sot eyes on for years."

" You mean Christo," said the other.

"I reckon he's the only red left in these parts, and 'arly riddance to him ! Jess show thet is an Injun bullit, and I've settled his 'count, sure's one and one make two."

" That savours too much o' wanton killing, Gunwad. I ain't no special grudge ag'in this Christo, though it may be I have leetle fellowship for the face. There be honest men, for all I can say, among the dusky-skins, and Christo may be one o' 'em. At any rate till I ketch him in red devilryment I'm not going to condemn him. Ah, Gunwad, I 'low I live by the chase, and if I do say it, who has no designment to boast o' the simple knack o' drawing bead on wildcat or painter, bear or stag, Old Danger never barks at the same creetur but once; but he never spits fire in the face o' any creetur that can't do more good by dying than living."

"Look here, Woodranger!" exclaimed Gunwad, impatiently, "I can see through yer logic. Ye air ag'in this law o' protecting deer."

" I'm ag'in the law that's ag'in man. 'Tain't natur to fill the woods with game, and then blaze the trees with notices not to tech a creetur. Mind you, I'm ag'in wanton killing, and him don't live as can say I ever drew bead on a deer out o' pure malice. I have noticed that it's the same chaps as makes these laws as are the ones to resort to wanton destruction. To kill jess for the fun o' killing is wanton. It is the great law o' natur for one kind to war on another, the strong on the weak, from the biggest brute to the smallest worm, and man wars on 'em all. If he must do so, let there be as much fairness as is consistent with human natur. No, I'm not a liker o' the law that professes to defend the helpless, but does it so the wanton slayer can get his glut o' slaughter in a fall's hunt. I — "

The Woodranger might have continued his rude philosophy much longer had not a movement of the hound on the cliff attracted their attention, and both men glanced upward to see, with surprise, Norman McNiel looking quietly down upon them.

" Hilloa! " exclaimed Gunwad, divining the situation at once, "here is the deer slayer, or I'm a fool. Stand where ye air, youngster! " raising his gun to his shoulder, as he spoke.

Back to top

CHAPTER III.

NORMAN MEETS HIS ENEMY.

on't make any wanton move," warned Woodranger" If I'm not mistaken the younker is one o' the Scotch settlers on the river, and he's a likely lad, or I'm no jedge o' human natur'."

" I jess want him to know he ain't going to play Injun with me," replied Gunwad. Then, speaking In a louder key to Norman, he said :

"Climb down hyur, youngster, and see thet ye air spry erbout it, for I don't think o' spending the night in these woods."

" I will be with you in a moment," said Norman, starting toward the west end of the cliff, where he could descend with comparative ease. He had overheard enough to understand that Gunwad would provc no friend to him, though he did not realise the deer reeve's full intent.

" One o' 'em condemned furriners !" muttered Gunwad " I'd as soon snap him up as thet copper-skin. Hi, there, youngster! be keerful how ye handle thet shooting iron," as Norman inadvertently lifted the weapon toward his shoulder in trying to avoid a bush.

" You have nothing to fear, as it isn't loaded. I—"

" Isn't loaded, eh ?" demanded the deer reeve. "Let me take it."

Norman handed him the firearm, as requested, and then turned to look at Woodranger, who was watching the scene in silence, with a look in his blue eyes that it was difficult to read.

" I reckon I've got all the evidence I shall need," said Gunwad, after hastily examining the gun. " You'll need to go with me to Chelmsford, youngster, to answer the grave charge of shooting deer out o' season. It'll only cost ye ten pounds, or forty days' work for the province. Better have waited ernother day afore ye took yer leetle hunt! "

" I have shot no deer, sir," replied Norman. " Neither have I hunted deer."

" Don't make yer case enny wuss by trying to lie out o' it. The circumstances air all ag'in ye. Air ye coming erlong quiet like, or shall I hev to call on Woodranger to help me ? "

" Where are you going to take me ?" asked Norman, feeling his first real alarm. " Grandfather will be worried about me if I go away without telling him — "

" Old man will be worrited, eh ? O' all the oxcuses to git out'n a bad fix thet's the tarnalest. D'ye hear thet, Woodranger ? "

Nettled by the words, Norman showed some of the spirit of the McNiels, exclaiming sharply:

"Sir, I have hunted no deer, shot no deer, and there is no reason why you should make me prisoner. I have transgressed no law, as far as I know."

" Ignerance is no excuse for breaking a law, youngster. The facts air all ag'in ye. Ain't this yer dog ? and weren't he chasing thet deer ? "

" He was chasing the deer, but surely you do not blame the hound for doing what his natural instinct told him to do ? To him all seasons are as one, and the laws of man unknown."

" A good p'int, lad," said Woodranger, speaking for the first time since Norman had reached the foot of the cliff.

" But it does not clear yer frills from the law made by honourable law-makers and sanctioned by good King George," retorted Gunwad, angrily. " Ye 'low yer dog was chasing the deer ? "

" I have not said he was my dog, sir. He came to my house about a week ago and would stay with u». I ---'

" 'Mounts to the same as if he wus yers. I s'pose ye deny this is yer gun and thet it's as empty as a last year's nutshell ? "

" The gun is mine, sir, and it is empty because I wasted my ammunition on a hawk an hour since. I had no more powder with me."

"A story jess erbout in keeping with the other. Afore ye take up lying fer a bizness I should 'vise ye to do a leetle practising. But I hev got evidence ernough, so kem erlong without enny more palaver."

Norman saw that it would be useless to remonstrate with the obstinate deer reeve, and he began to realise that he might have serious trouble with him before he could convince him and his friends of his innocence. Accordingly he hesitated before he said :

" I am innocent of this charge, sir, but if you will allow me to go home and tell sister and grandfather — "

" Go home! " again broke in Gunwad, who had no respect for another's feelings. " If thet ain't the coolest thing I ever heerd of. I s'pose ye think I'm innercent ernough to let ye take yer own way o' going to Chelmsford to answer to the grave charge o' shooting deer out o' season. Did ye ever see the match o' thet consarned audacity, Wood-ranger ?"

" It seems ag'in reason for me to think the lad means to play you double, Gunwad," said the Woodranger, deliberately. " It seems too bad to put the lad to this inconvanience. I 'low, down 'mong 'em strangers it'll be a purty sharp amazement for him to prove his innercence, but the lad's tongue tells a purty straight story. I disbelieve he was consarned in the killing o' the deer."

" Oh, ho ! so thet's the way the stick floats with ye, Woodranger ? Mebbe ye know crossways, but Captain Blanchard has the name o' being square and erbove board in his dealings. Ye can go down ef ye wanter, jess to show thet the deer jumped off'n the rock o' its own free will. Ha, ha ! thet's a kink fer ye to straighten."

" It would be easier done 'cording to my string o' knots, than to fairly prove the lad was to blame for its killing. I've heerd o' deer jumping off'n sich places out o' a pure wish to end their days. Up north, some years sence, I see, myself, an old sick buck march plumb down and sort o' throw hisself over a cliff o' rock, where the leetle life left in him was knocked flat. I was laying in ambushment for him, but seeing the creetur's intentions I jess waited to see what he would do. As I have said afore, I do not believe in wanton killing, and deer, 'cording to my mind, is next to the human family. This air rock has peculiar 'tractions for the low-spirited, and there are them as say the ghost o' poor Rimmon haunts the place, and it ain't so onreasonable in the light o' some other things."

Woodranger's speech had reference to the legend current among the Indians that a daughter of the mighty chief of the North, Chicorua, once fell in love with a Pennacook brave; but her dusky lover proved recreant to Rimmon, as the maiden was called, and she, unable to credit the stories told of her betrothed, sought this locality by stealth to learn if reports were true concerning him. Alas for her hopes ! she was soon only too well satisfied of their truthfulness, and, rather than return to her home, in her grief and disappointment, she courted death by leaping from this high rock. Hence the name Rock Rimmon.

" How long has it been sence the Indian killer turned philosopher and begun to preach ? " demanded Gunwad, whose coarse nature failed to appreciate the sentiments of his companion.

" Let's see," said Woodranger, ignoring the other's sneering words, " the law ag'in killing deer will be off afore you get the lad tried. If I remember right it was to last from the first day o' January to the first day o' August, and it being now nigh about six o'clock on the last day o' July, there are only six hours or so left — "

" What difference does thet make ?" cried Gunwad, with increasing anger. " Ef ye keep me hyur till to-morrow morning it'll be the same. But I ain't trying the youngster. Ef he'll kem erlong Squire Blanchard will settle his 'count."

"And give you half the fine, I s'pose," continued the imperturbable Woodranger, with his accustomed moderation.

" I shall 'arn it! " snapped the other. " But it's ye making me more trubble than he, Woodranger."

" I have a plan by which I may be able to more than even things with you, Gunwad, as bad as I have been. What time will you start for Chelmsford in the morning ?"

"An hour erfore sunup."

" Where do you think o' taking the lad to-night ? "

"Down to Shepley's."

" He's away, and the women folks might object to having a deer slayer in the house."

"I shall stay with him."

" They might object to you, too ! But that ain't neither here nor there. I reckon the lad's folks are going to be greatly consarned over his disappearance, so I have been thinking it would be better to let him go home now."

Gunwad was about to utter an angry speech, when the three were startled by the ringing note of a bugle sounding sharply on the still afternoon air. The first peal had barely died away before it was followed by two others in rapid succession, louder, clearer, and more prolonged each time.

" It's grandfather!" exclaimed Norman, excitedly. "There is something wrong at home."

Back to top

NORMAN MEETS HIS ENEMY.

| D |

on't make any wanton move," warned Woodranger" If I'm not mistaken the younker is one o' the Scotch settlers on the river, and he's a likely lad, or I'm no jedge o' human natur'."

" I jess want him to know he ain't going to play Injun with me," replied Gunwad. Then, speaking In a louder key to Norman, he said :

"Climb down hyur, youngster, and see thet ye air spry erbout it, for I don't think o' spending the night in these woods."

" I will be with you in a moment," said Norman, starting toward the west end of the cliff, where he could descend with comparative ease. He had overheard enough to understand that Gunwad would provc no friend to him, though he did not realise the deer reeve's full intent.

" One o' 'em condemned furriners !" muttered Gunwad " I'd as soon snap him up as thet copper-skin. Hi, there, youngster! be keerful how ye handle thet shooting iron," as Norman inadvertently lifted the weapon toward his shoulder in trying to avoid a bush.

" You have nothing to fear, as it isn't loaded. I—"

" Isn't loaded, eh ?" demanded the deer reeve. "Let me take it."

Norman handed him the firearm, as requested, and then turned to look at Woodranger, who was watching the scene in silence, with a look in his blue eyes that it was difficult to read.

" I reckon I've got all the evidence I shall need," said Gunwad, after hastily examining the gun. " You'll need to go with me to Chelmsford, youngster, to answer the grave charge of shooting deer out o' season. It'll only cost ye ten pounds, or forty days' work for the province. Better have waited ernother day afore ye took yer leetle hunt! "

" I have shot no deer, sir," replied Norman. " Neither have I hunted deer."

" Don't make yer case enny wuss by trying to lie out o' it. The circumstances air all ag'in ye. Air ye coming erlong quiet like, or shall I hev to call on Woodranger to help me ? "

" Where are you going to take me ?" asked Norman, feeling his first real alarm. " Grandfather will be worried about me if I go away without telling him — "

" Old man will be worrited, eh ? O' all the oxcuses to git out'n a bad fix thet's the tarnalest. D'ye hear thet, Woodranger ? "

Nettled by the words, Norman showed some of the spirit of the McNiels, exclaiming sharply:

"Sir, I have hunted no deer, shot no deer, and there is no reason why you should make me prisoner. I have transgressed no law, as far as I know."

" Ignerance is no excuse for breaking a law, youngster. The facts air all ag'in ye. Ain't this yer dog ? and weren't he chasing thet deer ? "

" He was chasing the deer, but surely you do not blame the hound for doing what his natural instinct told him to do ? To him all seasons are as one, and the laws of man unknown."

" A good p'int, lad," said Woodranger, speaking for the first time since Norman had reached the foot of the cliff.

" But it does not clear yer frills from the law made by honourable law-makers and sanctioned by good King George," retorted Gunwad, angrily. " Ye 'low yer dog was chasing the deer ? "

" I have not said he was my dog, sir. He came to my house about a week ago and would stay with u». I ---'

" 'Mounts to the same as if he wus yers. I s'pose ye deny this is yer gun and thet it's as empty as a last year's nutshell ? "

" The gun is mine, sir, and it is empty because I wasted my ammunition on a hawk an hour since. I had no more powder with me."

"A story jess erbout in keeping with the other. Afore ye take up lying fer a bizness I should 'vise ye to do a leetle practising. But I hev got evidence ernough, so kem erlong without enny more palaver."

Norman saw that it would be useless to remonstrate with the obstinate deer reeve, and he began to realise that he might have serious trouble with him before he could convince him and his friends of his innocence. Accordingly he hesitated before he said :

" I am innocent of this charge, sir, but if you will allow me to go home and tell sister and grandfather — "

" Go home! " again broke in Gunwad, who had no respect for another's feelings. " If thet ain't the coolest thing I ever heerd of. I s'pose ye think I'm innercent ernough to let ye take yer own way o' going to Chelmsford to answer to the grave charge o' shooting deer out o' season. Did ye ever see the match o' thet consarned audacity, Wood-ranger ?"

" It seems ag'in reason for me to think the lad means to play you double, Gunwad," said the Woodranger, deliberately. " It seems too bad to put the lad to this inconvanience. I 'low, down 'mong 'em strangers it'll be a purty sharp amazement for him to prove his innercence, but the lad's tongue tells a purty straight story. I disbelieve he was consarned in the killing o' the deer."

" Oh, ho ! so thet's the way the stick floats with ye, Woodranger ? Mebbe ye know crossways, but Captain Blanchard has the name o' being square and erbove board in his dealings. Ye can go down ef ye wanter, jess to show thet the deer jumped off'n the rock o' its own free will. Ha, ha ! thet's a kink fer ye to straighten."

" It would be easier done 'cording to my string o' knots, than to fairly prove the lad was to blame for its killing. I've heerd o' deer jumping off'n sich places out o' a pure wish to end their days. Up north, some years sence, I see, myself, an old sick buck march plumb down and sort o' throw hisself over a cliff o' rock, where the leetle life left in him was knocked flat. I was laying in ambushment for him, but seeing the creetur's intentions I jess waited to see what he would do. As I have said afore, I do not believe in wanton killing, and deer, 'cording to my mind, is next to the human family. This air rock has peculiar 'tractions for the low-spirited, and there are them as say the ghost o' poor Rimmon haunts the place, and it ain't so onreasonable in the light o' some other things."

Woodranger's speech had reference to the legend current among the Indians that a daughter of the mighty chief of the North, Chicorua, once fell in love with a Pennacook brave; but her dusky lover proved recreant to Rimmon, as the maiden was called, and she, unable to credit the stories told of her betrothed, sought this locality by stealth to learn if reports were true concerning him. Alas for her hopes ! she was soon only too well satisfied of their truthfulness, and, rather than return to her home, in her grief and disappointment, she courted death by leaping from this high rock. Hence the name Rock Rimmon.

" How long has it been sence the Indian killer turned philosopher and begun to preach ? " demanded Gunwad, whose coarse nature failed to appreciate the sentiments of his companion.

" Let's see," said Woodranger, ignoring the other's sneering words, " the law ag'in killing deer will be off afore you get the lad tried. If I remember right it was to last from the first day o' January to the first day o' August, and it being now nigh about six o'clock on the last day o' July, there are only six hours or so left — "

" What difference does thet make ?" cried Gunwad, with increasing anger. " Ef ye keep me hyur till to-morrow morning it'll be the same. But I ain't trying the youngster. Ef he'll kem erlong Squire Blanchard will settle his 'count."

"And give you half the fine, I s'pose," continued the imperturbable Woodranger, with his accustomed moderation.

" I shall 'arn it! " snapped the other. " But it's ye making me more trubble than he, Woodranger."

" I have a plan by which I may be able to more than even things with you, Gunwad, as bad as I have been. What time will you start for Chelmsford in the morning ?"

"An hour erfore sunup."

" Where do you think o' taking the lad to-night ? "

"Down to Shepley's."

" He's away, and the women folks might object to having a deer slayer in the house."

"I shall stay with him."

" They might object to you, too ! But that ain't neither here nor there. I reckon the lad's folks are going to be greatly consarned over his disappearance, so I have been thinking it would be better to let him go home now."

Gunwad was about to utter an angry speech, when the three were startled by the ringing note of a bugle sounding sharply on the still afternoon air. The first peal had barely died away before it was followed by two others in rapid succession, louder, clearer, and more prolonged each time.

" It's grandfather!" exclaimed Norman, excitedly. "There is something wrong at home."

Back to top

CHAPTER IV.

A PERILOUS PREDICAMENT.

F I should agree to answer for the lad's being on hand to-morrow morning an hour afore sunup, would you let him go home till then ?" asked Woodranger, the calmest one of the three, continuing the subject in his mind as if no interruption had occurred.

As a matter of fact, Gunwad had been puzzling himself over the best method to adopt in order to keep his prisoner safely until he could deliver him over to the proper authorities. Of a cowardly, treacherous nature, he naturally had little confidence in others. He believed the youthful captive to be a dangerous person, knowing well the valour of the McNiels, though he would not have acknowledged to any one that he feared him. Woodranger's proposition offered a way out of his dilemma without compromising himself, in case it should fail. Accordingly he asked, with an eagerness the woodsman did not fail to observe:

" Would ye dare take the risk, Woodranger ?"

" In season and out I have a knack o' following my words like a deerhound on the track o' a stag."

" I know it, Woodranger, so I hope ye won't harbour enny feeling fer my question. Ef ye say yc'll hev the youngster on hand at Shepley's at sunrise, I shall let him be in yer hands. But, mind ye, I shall look to ye fer my divvy in the reward if he's not on hand."

" I will walk along with you, lad," said the Woodranger, without replying to Gunwad, who remained watching them as they started away, muttering under his breath :

" 1 s'pose it's risky to let the youngster off in his care. Twenty-four dollars ain't to be picked up in these sand-banks every day, and I'm sure of it if I get the leetle fool to Chelmsford. It's a pity to let sich a good fat deer go to waste, and I've a mind to help myself to as much meat as I can carry off. It's no harm, seeing the killing is done, and I had no hand in it."

Glancing back as they were losing sight of Rock Rimmon, the Woodranger saw the deer reeve carrying out his intention, and laughed in his silent way.

Norman was not only willing but glad to have the company of the woodsman, whose fame he had heard so often mentioned by the settlers. As soon as they were beyond the hearing of Gunwad, he thanked his companion for his kindly intervention.

"I have nary desire for you to mention it, lad. But if you don't mind, you may tell me what you can of this deer killing. It may be only a concait o' mine, but my sarvices may be desirable afore you get out'n this affair. In that case it might be well for me to know the full particulars."

" You are very kind, Mr. — Mr. — "

" You may call me Woodranger, as the rest do. Time may have been when I had another name, but this one suits me best now. If you have been in these parts very long, you may have heard of me, though I trust not through any malicious person. I 'low none o' us are above having enemies. But I can see that you are anxious to get home, so tell me in a few words all you can about the deer."

"There is really little to tell, Mr. Woodranger. I was lying on the top of Rock Rimmon when I heard Archer bark, and I felt sure he had started a deer near Cedar Swamp. Soon after, I heard some one fire a gun. A moment later I saw Christo, the friendly Indian, coming toward the cliff, but at sight of me he turned and went the other way."

" So it was, as I thought, Christo who shot the deer. I'm sorry for that. The poor fellow has enough to answer for to pacify those who are determined to persecute him, simply because he is a red man. As if it was not enough to see the last foot o' territory belonging to his race stripped from his tribe, and the last o' his people driven off like leaves before an autumn wind."

This speech, coming from one whom he had heard of as an Indian fighter, seemed so strange to Norman th:it he exclaimed :

" So you are a friend to the Indians ! I supposed you hated them."

" We are all God's critters, lad, and I hate not even the lowest. Though it has been my fortune to be pitted ag'inst the dusky varmints in some clus quarters, I never drew bead on an Injun with a wanton thought. Mebbe on sich 'casions as Lovewell's fight, where the blood of white and red ran ankle deep, and that Injun fiend, bold Paugus — Hark! there's the horn ag'in! Your kin must be imxious about you. Ha! how the old bugle awakes old-time memories. But don't let me hinder you. I will meet you by the river to-morrer morning at sunrise, when we can start for Chelmsford. By the way, I wish you wouldn't say anything about Christo until I think it best."

Without further loss of time, Norman darted away from the Woodranger in a course which soon brought him in sight of the river.

On the opposite bank of the stream the young refugee discovered his grandfather, still holding to his lips the horn which was awakening the wild-wood with iis clear notes, as in years long since past it had rung over the hills and vales of his native land. At sight of Norman the aged bugler quickly removed his beloved instrument from his bearded lips, and while the echoes of the horn died slowly away he watched the approach of his grandson, who had pulled a canoe out from a bunch of bushes on the river bank and began his laborious trip across the rapid stream.

In the years of his vigorous manhood Robert MacDonald must have been a typical Highlander of Bonnie Scotland. As he stood there on the bank of the river, in the shifting light of the setting sun, his thin, whitened locks tossed in the gentle breeze, and his spare form half supported by a stout staff, he looked like one of the patriarchs of old appearing in the midst of that wild-wood scene. If the passage of time had left deep tracks across a brow once lofty and white as snow, if the lines about the mouth had deepened into wrinkles and the loss of teeth allowed an unpleasant compression of the lips, his clear blue eyes had lost little if any of their old-time lustre. His face kindled with a new fire, as he watched the approach of Norman.

" He's a noble laddie, every inch o' him ! " he mused, falling deeper into his native dialect as he continued : " Weel, alack an' a day, why should he no be a bonnie laddie wi' the bluid o' the MacDonalds an' McNiels coorsin' thro' his veins.

Shame upon the ane wha wud bring dishonour tae sic a fair name. He has nane o' his faither's weakness. He's MacDonald, wi' the best o' the McNeil only. Hoo handy he is wi' the skim-shell o' a craft that looks ower licht tae waft a feather ower the brawlin' burn."

" What can be the matter, grandfather, that you are so excited ?" asked Norman, as he ran the canoe upon the sandy bank and leaped out.

" It's the wee lassie. She left me awhile since tae look for the geese, an' she hasna cum back. She's been awa a lang time."

" I would not worry, grandfather. You know the geese have an inclination to get back to their kind at old Archie's. But I will lose no time in going to help Rilma fetch them home."

" Dae sae, my braw laddie, for I'm awfu' shilly the day. I canna tell thee it was a catamount's cry, but it did hae the soond tae my auld ear. But dinna credit ower muckle an auld man's ears, which dinna hear sue clear as on the day the redcoats mowed doon the auld clan at Glencoe."

At the mention of the word " catamount " Norman felt a sudden fear. He knew that a pair of the dreaded creatures had been seen in the vicinity several times of late, and that the presence of the geese would be likely to call them from their skulking-places in the dense forest skirting the few log houses near by. So leaving his aged relative to follow at his leisure, he bounded up the path leading to the house. Thinking of his empty gun, he was anxious to get a new supply of powder before putting himself in the pathway of any possible danger.

All of the dwellings of Tyng Township were of the most primitive character. There being no sawmill on the river at that period, the houses were built of hewn or unhewn logs, as the fancy or capacity for work of the owner dictated. The MacDonald cottage was smaller than the average, but the logs making its four walls had been hewn on the inside. The building was low-storied, and had small openings or loop-holes for windows, over which small mats of skins had been arranged to stop the apertures whenever it was desired. Originally the space of the building had been divided into only two apartments on the lower floor, but one of these had been subdivided, so there were two sleeping-rooms, one for Rilma and another for Mr. MacDonald, besides the living room, on the first floor. Norman occupied the unfinished loft for his bedchamber. Some of the houses of Tyng Township, or Old Harrytown, as it was quite as frequently called, had no floor, but in this hewn logs embedded in the sand and cemented along the seams or cracks afforded a solid foundation. A stone chimney at one end carried off the smoke from the wide-mouthed fireplace, which added a cheerfulness as well as genial warmth in cold weather to the primitive dwelling.

The furnishing of this typical frontier house was in keeping with its surroundings. The kitchen, or room first entered, which served as sitting-room, parlour, dining-room, and living apartment, was supplied with a three-legged table, a relic of ancient days that had been the gift of a neighbour, two old chairs which had been repaired from some broken ones, while a rude bench answered for a third seat. In one corner was an iron-bound chest, which had been the only piece of furniture, if it deserved that name, that had been brought from their native land. It held the plain wardrobes of the three. Hanging to the sooty crane in the fireplace was an iron pot, while in a niche in the rocky wall was a pewter pot, a frying-pan, and a skillet. In another small opening cut higher in the side of the building reposed the scanty supply of household utensils, a couple of pewter spoons, two wooden spoons, three knives, a couple of broken cups, a pewter dipper, and three wooden forks, with four rude plates made from two thicknesses of birch bark. There was also a small earthen pot.

Over the fireplace, hung on pegs driven in the chinks of the logs, was a long-barrelled musket of Scottish pattern, whose bruised stock and dinted Iron bespoke hard usage. This was the weapon Robert MacDonald had carried in the desperate

fight at Glencoe, when his clan had been completely routed by the English. Near by hung a powder-horn, grotesquely carved like an imp's head, and in close companionship was a bullet-pouch. Near it was another peg, the usual resting-place of an even more highly prized relic than any of these ancient pieces of property, namely, the bugle with which the old Highlander had called home the truant Norman.

The room, though rudely furnished, bore every trace of neatness and thrift, with an air of comfort in spite of its simple environments. The rough places in the walls were concealed by wreaths of leaves and ferns, and the table was bordered with a frill made of maple leaves knit together by their stems. On a shelf, made of pins driven into the wall, lay three books, one of them a volume of hymns, the second a collection of Scottish songs and ballads, while the third was a manuscript book of records of the Clan MacDonald, with some added notes of the McNiels.

The door was made by four small poles fastened together at the corners with wooden pins and strings cut from deer hide, the whole covered with a bear skin carefully tanned and the fur closely trimmed.

In his anxiety to go in search of Rilma, Norman did not stop to replenish his horn from the general supply of powder, but snatched that of his grand-father from its peg, and, loading his gun as he went along, left the house.

His home was near a small tributary of the Merrimack, which joined the main stream a short distance below the falls. The house stood a short distance back from what was considered the main road of the locality, a regularly laid out highway running from Namaske to the adjoining town of Nutfield or Londonderry, and following an old Indian trail. This road also led, a short distance (half a mile) above the falls, past two or three dwellings, to a more spacious log house which was the home of another Scottish family by the name of Stark. Archibald Stark, the head of this household, was a fine representative of his race, and he and his beautiful wife, with their seven children, four boys and three girls, were a typical frontier family, cheerful, rugged, hospitable, and progressive.

As the geese which had caused Rilma to leave her home had been the gift of Bertha Stark, the oldest daughter of the family, Norman hurried toward the home of these people, never doubting but he should find Rilma loitering there to continue some girlish gossip.

Soon after crossing the brook, however, his sharp eyes discovered fresh footprints in the soft earth near the bank of the stream and along a path leading to a small pond in the brook, where the water had been held back by a dam of fallen brushwood. He was sure the tracks had been made by Rilma.

" The geese have got away from her and gone to the Pool," he concluded. " I shall find her there. Better still, by waiting here I can head off the foolish geese from going back to their old home, as they will be pretty sure to do."

He had barely come to this conclusion, when he was startled by a loud squawk, quickly followed by a scream.

Something was wrong! He bounded along the narrow pathway toward the scene, while the outcries continued with increasing volume.

Meanwhile Rilma, having been obliged to go quite to Mr. Stark's house to find her truants, was returning with them, as Norman had imagined, when, on reaching the path leading to the little pond, the contrary creatures darted toward the Pool with loud cries. She followed, but not swift enough to stop the runaways.

The geese had gained the bank of the little pond, and she was following a few yards behind them, when a dark form sprang from a thicket bordering the pathway, and seized the foremost goose.

Thinking at first it was a dog attacking her geese, Rilma called out sharply to the brute, as she bounded toward the spot. But a second glance showed her not a dog but a big wildcat!

Nothing daunted by this startling discovery, the brave girl flourished the stick she carried in her hand and ran to defend the poor goose. So furiously did she rain her blows about the wildcat's head that it dropped its prey and sprang upon her ! With one sweep of its paw it tore the stout dress from her shoulder and left the marks of its cruel claws in her flesh. But the squawking goose, fluttering about on the ground, seemed a more tempting bait for the wildcat, which abandoned its attack on Rilma and sprang again on the goose.

Flung to the ground by the fierce assault of the beast, Rilma quickly regained her feet, and, seeing her favourite goose in deadly danger, she again attempted its rescue, although the blood was flowing in a stream from the wound in her shoulder. It was at this moment that Norman appeared on the scene.

Rilma and the catamount were engaged in too close a combat for him to shoot the creature without endangering her life, so he shouted for her to retreat, as he rushed to her assistance. But it was now impossible for her to do that. Having torn her dress nearly from her, and aroused at the sight of the blood flowing so freely, the enraged beast was in the act of fixing its terrible teeth in Rilma's body, when Norman pushed the muzzle of the gun into the wildcat's mouth, and pulled the trigger.

A dull report followed, and the catamount fell over dead. Norman was about to bear Rilma, who was now unconscious from pain and fright, away from the place, when a terrific snarl rang in his ears from over his head! Looking up, he saw to his horror a second wildcat, mate to the other, lying on the branch of an overhanging tree, and in the act of springing upon him !

Back to top

A PERILOUS PREDICAMENT.

| I |

F I should agree to answer for the lad's being on hand to-morrow morning an hour afore sunup, would you let him go home till then ?" asked Woodranger, the calmest one of the three, continuing the subject in his mind as if no interruption had occurred.

As a matter of fact, Gunwad had been puzzling himself over the best method to adopt in order to keep his prisoner safely until he could deliver him over to the proper authorities. Of a cowardly, treacherous nature, he naturally had little confidence in others. He believed the youthful captive to be a dangerous person, knowing well the valour of the McNiels, though he would not have acknowledged to any one that he feared him. Woodranger's proposition offered a way out of his dilemma without compromising himself, in case it should fail. Accordingly he asked, with an eagerness the woodsman did not fail to observe:

" Would ye dare take the risk, Woodranger ?"

" In season and out I have a knack o' following my words like a deerhound on the track o' a stag."

" I know it, Woodranger, so I hope ye won't harbour enny feeling fer my question. Ef ye say yc'll hev the youngster on hand at Shepley's at sunrise, I shall let him be in yer hands. But, mind ye, I shall look to ye fer my divvy in the reward if he's not on hand."

" I will walk along with you, lad," said the Woodranger, without replying to Gunwad, who remained watching them as they started away, muttering under his breath :

" 1 s'pose it's risky to let the youngster off in his care. Twenty-four dollars ain't to be picked up in these sand-banks every day, and I'm sure of it if I get the leetle fool to Chelmsford. It's a pity to let sich a good fat deer go to waste, and I've a mind to help myself to as much meat as I can carry off. It's no harm, seeing the killing is done, and I had no hand in it."

Glancing back as they were losing sight of Rock Rimmon, the Woodranger saw the deer reeve carrying out his intention, and laughed in his silent way.

Norman was not only willing but glad to have the company of the woodsman, whose fame he had heard so often mentioned by the settlers. As soon as they were beyond the hearing of Gunwad, he thanked his companion for his kindly intervention.

"I have nary desire for you to mention it, lad. But if you don't mind, you may tell me what you can of this deer killing. It may be only a concait o' mine, but my sarvices may be desirable afore you get out'n this affair. In that case it might be well for me to know the full particulars."

" You are very kind, Mr. — Mr. — "

" You may call me Woodranger, as the rest do. Time may have been when I had another name, but this one suits me best now. If you have been in these parts very long, you may have heard of me, though I trust not through any malicious person. I 'low none o' us are above having enemies. But I can see that you are anxious to get home, so tell me in a few words all you can about the deer."

"There is really little to tell, Mr. Woodranger. I was lying on the top of Rock Rimmon when I heard Archer bark, and I felt sure he had started a deer near Cedar Swamp. Soon after, I heard some one fire a gun. A moment later I saw Christo, the friendly Indian, coming toward the cliff, but at sight of me he turned and went the other way."

" So it was, as I thought, Christo who shot the deer. I'm sorry for that. The poor fellow has enough to answer for to pacify those who are determined to persecute him, simply because he is a red man. As if it was not enough to see the last foot o' territory belonging to his race stripped from his tribe, and the last o' his people driven off like leaves before an autumn wind."

This speech, coming from one whom he had heard of as an Indian fighter, seemed so strange to Norman th:it he exclaimed :

" So you are a friend to the Indians ! I supposed you hated them."

" We are all God's critters, lad, and I hate not even the lowest. Though it has been my fortune to be pitted ag'inst the dusky varmints in some clus quarters, I never drew bead on an Injun with a wanton thought. Mebbe on sich 'casions as Lovewell's fight, where the blood of white and red ran ankle deep, and that Injun fiend, bold Paugus — Hark! there's the horn ag'in! Your kin must be imxious about you. Ha! how the old bugle awakes old-time memories. But don't let me hinder you. I will meet you by the river to-morrer morning at sunrise, when we can start for Chelmsford. By the way, I wish you wouldn't say anything about Christo until I think it best."

Without further loss of time, Norman darted away from the Woodranger in a course which soon brought him in sight of the river.

On the opposite bank of the stream the young refugee discovered his grandfather, still holding to his lips the horn which was awakening the wild-wood with iis clear notes, as in years long since past it had rung over the hills and vales of his native land. At sight of Norman the aged bugler quickly removed his beloved instrument from his bearded lips, and while the echoes of the horn died slowly away he watched the approach of his grandson, who had pulled a canoe out from a bunch of bushes on the river bank and began his laborious trip across the rapid stream.

In the years of his vigorous manhood Robert MacDonald must have been a typical Highlander of Bonnie Scotland. As he stood there on the bank of the river, in the shifting light of the setting sun, his thin, whitened locks tossed in the gentle breeze, and his spare form half supported by a stout staff, he looked like one of the patriarchs of old appearing in the midst of that wild-wood scene. If the passage of time had left deep tracks across a brow once lofty and white as snow, if the lines about the mouth had deepened into wrinkles and the loss of teeth allowed an unpleasant compression of the lips, his clear blue eyes had lost little if any of their old-time lustre. His face kindled with a new fire, as he watched the approach of Norman.

" He's a noble laddie, every inch o' him ! " he mused, falling deeper into his native dialect as he continued : " Weel, alack an' a day, why should he no be a bonnie laddie wi' the bluid o' the MacDonalds an' McNiels coorsin' thro' his veins.

Shame upon the ane wha wud bring dishonour tae sic a fair name. He has nane o' his faither's weakness. He's MacDonald, wi' the best o' the McNeil only. Hoo handy he is wi' the skim-shell o' a craft that looks ower licht tae waft a feather ower the brawlin' burn."

" What can be the matter, grandfather, that you are so excited ?" asked Norman, as he ran the canoe upon the sandy bank and leaped out.

" It's the wee lassie. She left me awhile since tae look for the geese, an' she hasna cum back. She's been awa a lang time."

" I would not worry, grandfather. You know the geese have an inclination to get back to their kind at old Archie's. But I will lose no time in going to help Rilma fetch them home."

" Dae sae, my braw laddie, for I'm awfu' shilly the day. I canna tell thee it was a catamount's cry, but it did hae the soond tae my auld ear. But dinna credit ower muckle an auld man's ears, which dinna hear sue clear as on the day the redcoats mowed doon the auld clan at Glencoe."